Luke 18:9-14

This parable is one that lives rent-free in my head and I’ve never really been sure why. It is not one of the more well-known or well-loved, not often depicted in art or remembered in hymns. But in reading a blog post by the dean of Berkley Divinity School at Yale, I think I’m a little closer to figuring it out. Dr. McGowan points out that, although we have all kinds of cultural biases against Pharisees, they were not the villains we have made them out to be. The Pharisees were not roving bands of bullies looking for a Messiah to heckle but rather, as Dr. McGowan puts it, they were serious, committed, faithful Jewish believers. They were the church people of their day, the ones who prayed fervently and consistently and read their Bible every day and took seriously their commitments to care for the poor and offer the first fruits of their labor to God. The Pharisees were likely educated, literate, and passionate about their studies. They were easy to spot by the way they dressed in clothing that carried layers of symbolic meaning. They were understood in their communities to be people who take God seriously and were probably the people many neighbors and family members came to for prayer or advice or scripture interpretation. Pharisees were the kind of people, within their time and place and religion, that I strive to be now. Serious and committed to the faith. It’s the same hope that we have for our church, the same prayer I have for each of you. That we take our Bible seriously, that we take our prayer seriously, that we give sacrificially and remain committed to serving the poor and the vulnerable. The people the Pharisees were trying to be, are the people we are trying to be.

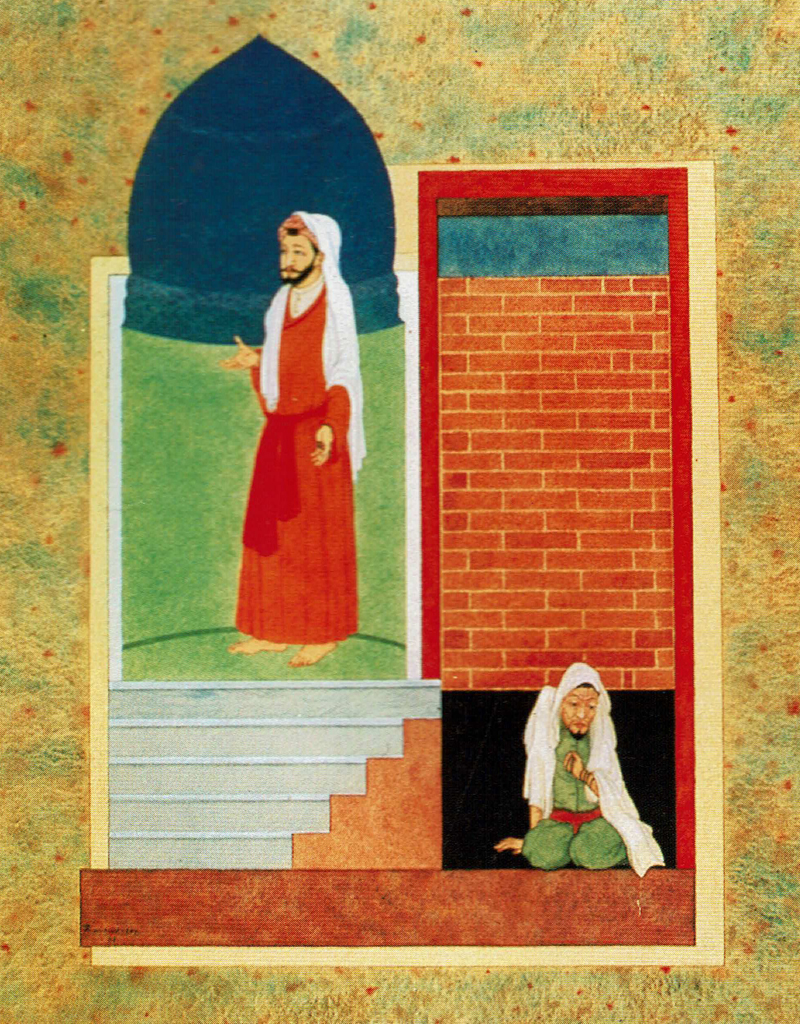

What the Pharisee is thanking God for sounds arrogant and a little ridiculous to our ears. Thank you God that I am not like other people, he says, listing some examples of the unsavory characters he is glad not to be. But then he lists the reasons he is not like those other people. He fasts twice a week, he gives a tenth of all his income, he obviously prays and makes regular visits to the Temple, and as a Pharisee he probably studies and recites scripture almost constantly. Basically, he comes to church every Sunday, he pays his pledge every month, and he shows up to Bible study consistently. He is a righteous, faithful, dutiful person. His contributions feed and care for people like the widow in last week’s parable, and his strict observance of Torah preserves precious religious and ethnic heritage amid an occupation by a pagan foreign empire. He is not like other people, and in a lot of ways the world is better for it.

We do not want to identify with the Pharisee, because we understand Pharisees to be stuck up hypocritical legalistic bullies who got our Savior killed. But the truth is, most of us are much more like him than we would like to believe. In fact, if more of us lived more like him, life might not be so hard for so many people. If everyone shared their wealth consistently and sacrificially in gratitude to God, every church would have enough to sustain themselves AND feed the hungry, clothe the naked, and shelter the lonely. If everyone took spiritual discipline seriously, if everyone knew their Bible and asked questions and challenged teachings like the Pharisees did, perhaps we would have a society that didn’t cause people to be hungry, naked, and alone. I feel sure the world would be better if we did not have systems that produced thieves, rogues, adulterers, and abusers who prey on the vulnerable in the service of unjust systems like so many tax collectors in the time of Jesus.

But it is the tax collector whom Jesus calls justified. The tax collector who does not feel worthy even to look up toward heaven, who is wealthy and powerful and colluding with a violent regime, went home justified and will be exalted, according to Jesus.

Tax collectors were despised by many in the Jewish community in Jesus’s lifetime. They were understood as sympathizers to the Roman Empire, betraying their own people for money. Many of them were extortionists, collecting additional fees above and beyond the intentionally oppressive taxes demanded by the Emperor. They were not welcome in many communal spaces, and it’s likely that disapproving families would cut ties with them. But they were not pitiable figures by any means. Tax collectors of the Roman Empire were wealthy, they enjoyed the protection of the Roman military and the favor of local politicians who benefited from their work, and their children grew up well fed and well-positioned. This was a life they chose, knowing full-well what social consequences awaited them once they did.

Imagine what it must have taken for a man with everything, a man with wealth and status and power, to stand alone before God and beg for mercy. It would not have earned him any kind of affection or forgiveness from his peers. It would not have impressed the Pharisees or the scribes. It would not have earned him an invitation back into the fold of family members and friends who hated what he had become. It might have even had financial consequences, if his behavior was viewed as a sign of weakness by those who expected him to intimidate and extort his community. From an earthly perspective, the tax collector has nothing to gain, and everything to lose. But from Jesus’s perspective, from the heavenly perspective, his humility exalts him. He is aware of his great need for divine mercy, and he is justified.

It is very tempting to make one of these characters a stand-in for everyone we disapprove of and to find ourselves in the other character. But no matter who we choose, we end up in the same boat with Jesus’s original audience, those who trusted in themselves that they were righteous and regarded others with contempt. If we see ourselves in the Pharisee, good church people doing our best, we risk the same self-righteousness. If we see ourselves in the tax collector, sinners relying on the mercy of God, then we’ve fallen right back into that same trap, placing ourselves among the ones Jesus calls justified and exalted. It is a double-bind, an impossible binary, because the truth is it is not up to us to decide who is righteous and who is not, who is justified and who is not, who deserves mercy and who does not. That is in God’s hands. It is Jesus who is our judge, and our feeble attempts to judge one another will always fall short of the truth. As Lutheran Pastor Matthew Weber once said, every time we draw a line between us and others, Jesus is always on the other side of it.1 Jesus is always on the other side, and Jesus is always trying to help us erase the line. Without the line between Pharisees and tax collectors, between us and them, all that remains are a bunch of beloved sinners, wrapped up in the arms of a merciful God. Thank God for that.

- This statement was quoted by Lutheran Pastor Nadia Bolz Weber in her book Pastrix, where she attributes the statement to her then-husband Matthew Weber ↩︎